During the Civil War, the infrastructure of St. Louis had suffered from vast neglect; and in 1866, a cholera epidemic riddled with typhoid fever raged in certain quarters of the city, killing more than 3,500 people.

After this disaster, the St. Louis Board of Health was formed and was given the power to create and enforce sanitary regulations and monitor the activities of certain polluting industries.

To rectify some of the problems with the water system, a new waterworks was built in north St. Louis in 1871, accompanied by a large reservoir at Compton Hill and a standpipe at Grand Avenue. However, water quality problems continued due to high demand and the dumping of waste upriver from the waterworks.

St. Louis did not filter its water supply and, like many communities at the time, suffered fromrecurring episodes of waterborne disease. In 1900, St. Louis health officials reported an average of 29 typhoid deaths per 100,000 people.

Although St. Louis and other cities fretted about healthy drinking water, they lacked the motivation to clean up local industrial and sewage pollution, which was a by-product of a striving industralized city. A scientist with the United States Geological Survey complained about the agonizingly slow rise of an “effective public sentiment” against the pollution of rivers, lakes and harbors.

St. Louis (like Kansas City) discharged its sewers directly into a large river, (albeit downstream of its drinking water intake), and (like Kansas City) had no significant wastewater treatment facilities until the second half of the twentieth century.

It seemed that St. Louis residents worried more about the thick smoke hanging over their coal-burning neighborhoods than about water pollution. When word of the Fair spread, this stimulated a major smoke abatement movement. However, this initiative had more to do with polishing the city’s image than with concerns over public health.

In 1900, high-profile water pollution concerns flowed into Missouri when Chicago, in an attempt to

protect its Lake Michigan water supply, diverted its sewage into the Des Plaines River. This river

fed into the Mississippi, from which St. Louis drew its drinking water, albeit hundreds of miles

downstream. St. Louis sued the state of Illinois, but a judge eventually dismissed the case, ruling

that the sewage had been adequately diluted and diminished by the time it reached Missouri.

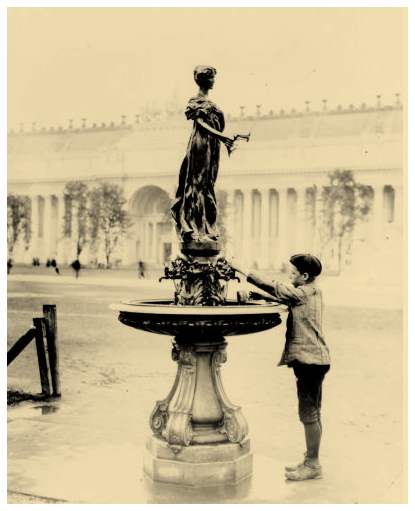

Prior to the Fair, officials and civic leaders were concerned that the waters falling from The Cascades, would not be clear. The Mississippi River, the prime source for the city's water, often flowed with a brown hue at its source.

The World’s Fair Committee paid workers to straighten and bury about a mile of the River des Peres, which meandered across the 1,300-acre fairgrounds. Some historians suggest that the stream was diverted underground at least partly to hide its embarrassingly polluted state and stench from

fairgoers.

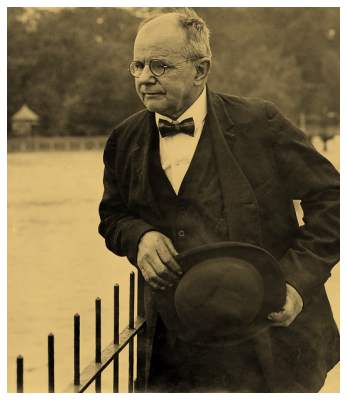

City workers installed a newly patented coagulation process to ensure water clarity. John F. Wixford, a graduate of Washington University with a degree in engineering. Wixford adjusted the treatment method used in Quincy, Ill., by greatly increasing the amount of lime used to get sediment to sink much more quickly to the bottom of settling tanks. When the city began using Wixford's formula of lime and iron oxide, for the waterworks at Chain of Rocks; the water ran clear, and did so only one month before the Fair opened in Forest Park.

Because of the provision of outside water reflected some concern with the safety of the public water supply and its surface source, the Mississippi River; the Exposition Company, chose to provide alternative drinking water for the event, hauling water in by the train car load from the artesian wells in De Soto, Missouri, which was nick-named- Fountain City.

Visitors at the 1904 World's Fair were dispensed a cup of water by dropping a penny into a machine.