Racism is a belief or doctrine that inherent differences among the various human races determine cultural or individual achievement,usually involving the idea that one's own race is superior and has the right to rule others. It can also be a policy, system of government, etc., based upon or fostering such a doctrine; discrimination. Many see the most obvious definition; a hatred or intolerance of another race or other races.

The Civil Rights Act of 1875, introduced by Charles Sumner and Benjamin F. Butler, stipulated a guarantee that everyone, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, was entitled to the same treatment in public accommodations, such as inns, public transportation, theaters, and other places of recreation. This Act had little impact.

African American and Native American groups protested their exclusion from the 1893 Chicago fair. Frederick Douglas spoke at the fair to address the issue of racism.

As the 1904 World's Fair was only forty year after the Civil War, racism was prevalent in the United States. The black community had little leverage and the Jim Crow laws did not help the problems.

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws in the United States enacted between 1876 and 1965. They mandated racial segregation in all public facilities, with a supposedly "separate but equal" status for black Americans. In reality, this led to treatment and accommodations that were usually inferior to those provided for white Americans, systematizing a number of economic, educational and social disadvantages.

Fair President, David R. Francis wanted the Fair to be enjoyed by people of all races. The problem with that was not all venders, employees, and officials had the same agenda.

Many prominent African-American leaders had called for a boycott of the games to protest racial segregation of the events in St. Louis. An integrated audience was not allowed at either the Olympics or the World's Fair as the organizers had constructed segregated Jim Crow facilities for their spectators. Yet, many came and enjoyed the Fair. One bold athlete- George Poage (see photo at bottom of page), chose to compete and became the first African-American to medal in the Games by winning the bronze in both the 220-yard and 440-yard hurdles.

Though the 1904 Olympics were dominated by a mostly `white,' contingency, Frank Pierce became the first American Indian Olympian, running in the marathon and setting the stage for Jim Thorpe to dominate the 1912 games. Two Zulus, working the Fair as part of a big Boer War exhibit, placed fifth and 12th in the marathon.

All was not negative, one of the most popular Pike attractions was Dr. William Key's million dollar educated horse- Beautiful Jim Key. The attraction make more than four times its cost. It was said that 4 million people met Dr. Key and his famous horse. Annie Turnbo Malone, an African American business woman; she sold hair products at the Fair and later became a millionaire. Scott Joplin, Lewis F. Muir, Lewis Chauvin, and other musicians visited or played at the Fair. Though ragtime didn't have the `snobappeal' of classical and marching band music, it was extremely popular and thrived on the Pike.

The worst account of racism was the indignancy of the human Zoos (called `People Shows'). They were a means of bolstering popular racism by connecting it to scientific racismage." Sadly this practice continued as late as 1958 at the Brussels' World Fair.

Though the 47-acre Philippine Village did portray the more advanced Philippine people in a non-zoo manner, by showcasing their hospitals, art, etc. The most popular attraction was observing the `lesser advanced' tribes such as the Igorats and Moros in `natural' settings.

They were shown as cultural inferior, and animal-like. The `primitives' were also `encourage' to partake in Western Civilization's cultures that they had no familiarity with whatsoever. This came to a large fruition on the Anthropology Days.

Amateur Athletic Union founder James E. Sullivan, who had racist views, thought that the Anthropology Days (athlete games), were at least partially successful. Sullivan considered the natives' failure to beat the Olympic record for the javelin a sure sign of racial inferiority rather than an aversion to an apparatus never before encountered.

Miss Jessie Davis, the hostess of the Arizona Bulding denied a `black' couple an opportunity to be married in the state building (as per her ad), because they were of `color.'

The National Association of Colored Women was holding their conference here July 13," da Silva recalls. "One of the women scouted around on site ahead of the conference and found out she couldn't get served anywhere; 2,000 women said 'hell, no. We won't go,' and they pulled out of St. Louis.

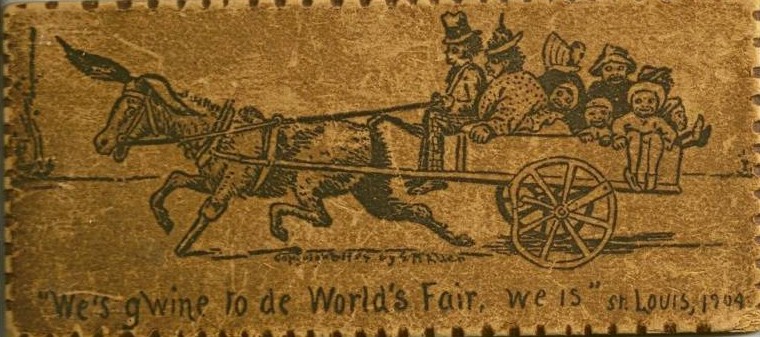

Another racist aspect of the Fair and society in general was `black' `humor;' these`comical' illustrations usually portrayed `black' Americans as raggedly dressed and uneducated. The below comic is a plaque that reads: "We's g'wine to de world's fair, we is." This illustration shows in a nutshell how some Americans thought of African Americans. These type of cartoons could be found on postcards, tin trays, and souvenir plaques. It would many decades of small amount of positive gains, as well as re-education to change people's minds.

Though racists views and sterotypes did tarnish the magnificent grandeur of he Fair, it can not erase the positives that helped push America forward.

August 1, 1904, was supposed to be a celebration of 'Negro Day,' A committee of African-American's headed by attorney Walter M. Farmer, abandoned the celebration, due to too much discrimination at the Fair- in particular, restaurants and eateries. Colonel Marshall (of the Eighth Illinois, received a message stating that his 900 soldiers would not be allowed to bunk at the Fair’s barracks, and would have to provide their own tents and cooking outfit.